Chapter 6. Collaborating with other people

Table of Contents

- Mercurial's web interface

- Collaboration models

- The technical side of sharing

- Informal sharing with hg serve

- Using the Secure Shell (ssh) protocol

- Serving over HTTP using CGI

- System-wide configuration

As a completely decentralised tool, Mercurial doesn't impose any policy on how people ought to work with each other. However, if you're new to distributed revision control, it helps to have some tools and examples in mind when you're thinking about possible workflow models.

Mercurial's web interface

Mercurial has a powerful web interface that provides several useful capabilities.

For interactive use, the web interface lets you browse a single repository or a collection of repositories. You can view the history of a repository, examine each change (comments and diffs), and view the contents of each directory and file. You can even get a view of history that gives a graphical view of the relationships between individual changes and merges.

Also for human consumption, the web interface provides Atom and RSS feeds of the changes in a repository. This lets you “subscribe” to a repository using your favorite feed reader, and be automatically notified of activity in that repository as soon as it happens. I find this capability much more convenient than the model of subscribing to a mailing list to which notifications are sent, as it requires no additional configuration on the part of whoever is serving the repository.

The web interface also lets remote users clone a repository, pull changes from it, and (when the server is configured to permit it) push changes back to it. Mercurial's HTTP tunneling protocol aggressively compresses data, so that it works efficiently even over low-bandwidth network connections.

The easiest way to get started with the web interface is to use your web browser to visit an existing repository, such as the master Mercurial repository at http://www.selenic.com/repo/hg.

If you're interested in providing a web interface to your own repositories, there are several good ways to do this.

The easiest and fastest way to get started in an informal environment is to use the hg serve command, which is best suited to short-term “lightweight” serving. See the section called “Informal sharing with hg serve” below for details of how to use this command.

For longer-lived repositories that you'd like to have permanently available, there are several public hosting services available. Some are free to open source projects, while others offer paid commercial hosting. An up-to-date list is available at http://www.selenic.com/mercurial/wiki/index.cgi/MercurialHosting.

If you would prefer to host your own repositories, Mercurial has built-in support for several popular hosting technologies, most notably CGI (Common Gateway Interface), and WSGI (Web Services Gateway Interface). See the section called “Serving over HTTP using CGI” for details of CGI and WSGI configuration.

Collaboration models

With a suitably flexible tool, making decisions about workflow is much more of a social engineering challenge than a technical one. Mercurial imposes few limitations on how you can structure the flow of work in a project, so it's up to you and your group to set up and live with a model that matches your own particular needs.

Factors to keep in mind

The most important aspect of any model that you must keep in mind is how well it matches the needs and capabilities of the people who will be using it. This might seem self-evident; even so, you still can't afford to forget it for a moment.

I once put together a workflow model that seemed to make perfect sense to me, but that caused a considerable amount of consternation and strife within my development team. In spite of my attempts to explain why we needed a complex set of branches, and how changes ought to flow between them, a few team members revolted. Even though they were smart people, they didn't want to pay attention to the constraints we were operating under, or face the consequences of those constraints in the details of the model that I was advocating.

Don't sweep foreseeable social or technical problems under the rug. Whatever scheme you put into effect, you should plan for mistakes and problem scenarios. Consider adding automated machinery to prevent, or quickly recover from, trouble that you can anticipate. As an example, if you intend to have a branch with not-for-release changes in it, you'd do well to think early about the possibility that someone might accidentally merge those changes into a release branch. You could avoid this particular problem by writing a hook that prevents changes from being merged from an inappropriate branch.

Informal anarchy

I wouldn't suggest an “anything goes” approach as something sustainable, but it's a model that's easy to grasp, and it works perfectly well in a few unusual situations.

As one example, many projects have a loose-knit group of collaborators who rarely physically meet each other. Some groups like to overcome the isolation of working at a distance by organizing occasional “sprints”. In a sprint, a number of people get together in a single location (a company's conference room, a hotel meeting room, that kind of place) and spend several days more or less locked in there, hacking intensely on a handful of projects.

A sprint or a hacking session in a coffee shop are the perfect places to use the hg serve command, since hg serve does not require any fancy server infrastructure. You can get started with hg serve in moments, by reading the section called “Informal sharing with hg serve” below. Then simply tell the person next to you that you're running a server, send the URL to them in an instant message, and you immediately have a quick-turnaround way to work together. They can type your URL into their web browser and quickly review your changes; or they can pull a bugfix from you and verify it; or they can clone a branch containing a new feature and try it out.

The charm, and the problem, with doing things in an ad hoc fashion like this is that only people who know about your changes, and where they are, can see them. Such an informal approach simply doesn't scale beyond a handful people, because each individual needs to know about n different repositories to pull from.

A single central repository

For smaller projects migrating from a centralised revision control tool, perhaps the easiest way to get started is to have changes flow through a single shared central repository. This is also the most common “building block” for more ambitious workflow schemes.

Contributors start by cloning a copy of this repository. They can pull changes from it whenever they need to, and some (perhaps all) developers have permission to push a change back when they're ready for other people to see it.

Under this model, it can still often make sense for people to pull changes directly from each other, without going through the central repository. Consider a case in which I have a tentative bug fix, but I am worried that if I were to publish it to the central repository, it might subsequently break everyone else's trees as they pull it. To reduce the potential for damage, I can ask you to clone my repository into a temporary repository of your own and test it. This lets us put off publishing the potentially unsafe change until it has had a little testing.

If a team is hosting its own repository in this kind of scenario, people will usually use the ssh protocol to securely push changes to the central repository, as documented in the section called “Using the Secure Shell (ssh) protocol”. It's also usual to publish a read-only copy of the repository over HTTP, as in the section called “Serving over HTTP using CGI”. Publishing over HTTP satisfies the needs of people who don't have push access, and those who want to use web browsers to browse the repository's history.

A hosted central repository

A wonderful thing about public hosting services like Bitbucket is that not only do they handle the fiddly server configuration details, such as user accounts, authentication, and secure wire protocols, they provide additional infrastructure to make this model work well.

For instance, a well-engineered hosting service will let people clone their own copies of a repository with a single click. This lets people work in separate spaces and share their changes when they're ready.

In addition, a good hosting service will let people communicate with each other, for instance to say “there are changes ready for you to review in this tree”.

Working with multiple branches

Projects of any significant size naturally tend to make progress on several fronts simultaneously. In the case of software, it's common for a project to go through periodic official releases. A release might then go into “maintenance mode” for a while after its first publication; maintenance releases tend to contain only bug fixes, not new features. In parallel with these maintenance releases, one or more future releases may be under development. People normally use the word “branch” to refer to one of these many slightly different directions in which development is proceeding.

Mercurial is particularly well suited to managing a number of simultaneous, but not identical, branches. Each “development direction” can live in its own central repository, and you can merge changes from one to another as the need arises. Because repositories are independent of each other, unstable changes in a development branch will never affect a stable branch unless someone explicitly merges those changes into the stable branch.

Here's an example of how this can work in practice. Let's say you have one “main branch” on a central server.

$hg init main$cd main$echo 'This is a boring feature.' > myfile$hg commit -A -m 'We have reached an important milestone!'adding myfile

People clone it, make changes locally, test them, and push them back.

Once the main branch reaches a release milestone, you can use the hg tag command to give a permanent name to the milestone revision.

$hg tag v1.0$hg tipchangeset: 1:47867ad65069 tag: tip user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com> date: Tue May 05 06:55:20 2009 +0000 summary: Added tag v1.0 for changeset cefe13bbe8af$hg tagstip 1:47867ad65069 v1.0 0:cefe13bbe8af

Let's say some ongoing development occurs on the main branch.

$cd ../main$echo 'This is exciting and new!' >> myfile$hg commit -m 'Add a new feature'$cat myfileThis is a boring feature. This is exciting and new!

Using the tag that was recorded at the milestone, people who clone that repository at any time in the future can use hg update to get a copy of the working directory exactly as it was when that tagged revision was committed.

$cd ..$hg clone -U main main-old$cd main-old$hg update v1.01 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved$cat myfileThis is a boring feature.

In addition, immediately after the main branch is tagged, we can then clone the main branch on the server to a new “stable” branch, also on the server.

$cd ..$hg clone -rv1.0 main stablerequesting all changes adding changesets adding manifests adding file changes added 1 changesets with 1 changes to 1 files updating working directory 1 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

If we need to make a change to the stable branch, we can then clone that repository, make our changes, commit, and push our changes back there.

$hg clone stable stable-fixupdating working directory 1 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved$cd stable-fix$echo 'This is a fix to a boring feature.' > myfile$hg commit -m 'Fix a bug'$hg pushpushing to /tmp/branching3sONTi/stable searching for changes adding changesets adding manifests adding file changes added 1 changesets with 1 changes to 1 files

Because Mercurial repositories are independent, and Mercurial doesn't move changes around automatically, the stable and main branches are isolated from each other. The changes that we made on the main branch don't “leak” to the stable branch, and vice versa.

We'll often want all of our bugfixes on the stable branch to show up on the main branch, too. Rather than rewrite a bugfix on the main branch, we can simply pull and merge changes from the stable to the main branch, and Mercurial will bring those bugfixes in for us.

$cd ../main$hg pull ../stablepulling from ../stable searching for changes adding changesets adding manifests adding file changes added 1 changesets with 1 changes to 1 files (+1 heads) (run 'hg heads' to see heads, 'hg merge' to merge)$hg mergemerging myfile 0 files updated, 1 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved (branch merge, don't forget to commit)$hg commit -m 'Bring in bugfix from stable branch'$cat myfileThis is a fix to a boring feature. This is exciting and new!

The main branch will still contain changes that are not on the stable branch, but it will also contain all of the bugfixes from the stable branch. The stable branch remains unaffected by these changes, since changes are only flowing from the stable to the main branch, and not the other way.

Feature branches

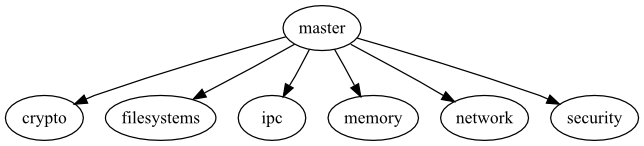

For larger projects, an effective way to manage change is to break up a team into smaller groups. Each group has a shared branch of its own, cloned from a single “master” branch used by the entire project. People working on an individual branch are typically quite isolated from developments on other branches.

When a particular feature is deemed to be in suitable shape, someone on that feature team pulls and merges from the master branch into the feature branch, then pushes back up to the master branch.

The release train

Some projects are organized on a “train” basis: a release is scheduled to happen every few months, and whatever features are ready when the “train” is ready to leave are allowed in.

This model resembles working with feature branches. The difference is that when a feature branch misses a train, someone on the feature team pulls and merges the changes that went out on that train release into the feature branch, and the team continues its work on top of that release so that their feature can make the next release.

The Linux kernel model

The development of the Linux kernel has a shallow hierarchical structure, surrounded by a cloud of apparent chaos. Because most Linux developers use git, a distributed revision control tool with capabilities similar to Mercurial, it's useful to describe the way work flows in that environment; if you like the ideas, the approach translates well across tools.

At the center of the community sits Linus Torvalds, the creator of Linux. He publishes a single source repository that is considered the “authoritative” current tree by the entire developer community. Anyone can clone Linus's tree, but he is very choosy about whose trees he pulls from.

Linus has a number of “trusted lieutenants”. As a general rule, he pulls whatever changes they publish, in most cases without even reviewing those changes. Some of those lieutenants are generally agreed to be “maintainers”, responsible for specific subsystems within the kernel. If a random kernel hacker wants to make a change to a subsystem that they want to end up in Linus's tree, they must find out who the subsystem's maintainer is, and ask that maintainer to take their change. If the maintainer reviews their changes and agrees to take them, they'll pass them along to Linus in due course.

Individual lieutenants have their own approaches to reviewing, accepting, and publishing changes; and for deciding when to feed them to Linus. In addition, there are several well known branches that people use for different purposes. For example, a few people maintain “stable” repositories of older versions of the kernel, to which they apply critical fixes as needed. Some maintainers publish multiple trees: one for experimental changes; one for changes that they are about to feed upstream; and so on. Others just publish a single tree.

This model has two notable features. The first is that it's “pull only”. You have to ask, convince, or beg another developer to take a change from you, because there are almost no trees to which more than one person can push, and there's no way to push changes into a tree that someone else controls.

The second is that it's based on reputation and acclaim. If you're an unknown, Linus will probably ignore changes from you without even responding. But a subsystem maintainer will probably review them, and will likely take them if they pass their criteria for suitability. The more “good” changes you contribute to a maintainer, the more likely they are to trust your judgment and accept your changes. If you're well-known and maintain a long-lived branch for something Linus hasn't yet accepted, people with similar interests may pull your changes regularly to keep up with your work.

Reputation and acclaim don't necessarily cross subsystem or “people” boundaries. If you're a respected but specialised storage hacker, and you try to fix a networking bug, that change will receive a level of scrutiny from a network maintainer comparable to a change from a complete stranger.

To people who come from more orderly project backgrounds, the comparatively chaotic Linux kernel development process often seems completely insane. It's subject to the whims of individuals; people make sweeping changes whenever they deem it appropriate; and the pace of development is astounding. And yet Linux is a highly successful, well-regarded piece of software.

Pull-only versus shared-push collaboration

A perpetual source of heat in the open source community is whether a development model in which people only ever pull changes from others is “better than” one in which multiple people can push changes to a shared repository.

Typically, the backers of the shared-push model use tools that actively enforce this approach. If you're using a centralised revision control tool such as Subversion, there's no way to make a choice over which model you'll use: the tool gives you shared-push, and if you want to do anything else, you'll have to roll your own approach on top (such as applying a patch by hand).

A good distributed revision control tool will support both models. You and your collaborators can then structure how you work together based on your own needs and preferences, not on what contortions your tools force you into.

Where collaboration meets branch management

Once you and your team set up some shared repositories and start propagating changes back and forth between local and shared repos, you begin to face a related, but slightly different challenge: that of managing the multiple directions in which your team may be moving at once. Even though this subject is intimately related to how your team collaborates, it's dense enough to merit treatment of its own, in Chapter 8, Managing releases and branchy development.

The technical side of sharing

The remainder of this chapter is devoted to the question of sharing changes with your collaborators.

Informal sharing with hg serve

Mercurial's hg serve command is wonderfully suited to small, tight-knit, and fast-paced group environments. It also provides a great way to get a feel for using Mercurial commands over a network.

Run hg serve inside a

repository, and in under a second it will bring up a specialised

HTTP server; this will accept connections from any client, and

serve up data for that repository until you terminate it.

Anyone who knows the URL of the server you just started, and can

talk to your computer over the network, can then use a web

browser or Mercurial to read data from that repository. A URL

for a hg serve instance running

on a laptop is likely to look something like

http://my-laptop.local:8000/.

The hg serve command is not a general-purpose web server. It can do only two things:

In particular, hg serve won't allow remote users to modify your repository. It's intended for read-only use.

If you're getting started with Mercurial, there's nothing to prevent you from using hg serve to serve up a repository on your own computer, then use commands like hg clone, hg incoming, and so on to talk to that server as if the repository was hosted remotely. This can help you to quickly get acquainted with using commands on network-hosted repositories.

A few things to keep in mind

Because it provides unauthenticated read access to all clients, you should only use hg serve in an environment where you either don't care, or have complete control over, who can access your network and pull data from your repository.

The hg serve command knows nothing about any firewall software you might have installed on your system or network. It cannot detect or control your firewall software. If other people are unable to talk to a running hg serve instance, the second thing you should do (after you make sure that they're using the correct URL) is check your firewall configuration.

By default, hg serve

listens for incoming connections on port 8000. If another

process is already listening on the port you want to use, you

can specify a different port to listen on using the -p option.

Normally, when hg serve

starts, it prints no output, which can be a bit unnerving. If

you'd like to confirm that it is indeed running correctly, and

find out what URL you should send to your collaborators, start

it with the -v

option.

Using the Secure Shell (ssh) protocol

You can pull and push changes securely over a network

connection using the Secure Shell (ssh)

protocol. To use this successfully, you may have to do a little

bit of configuration on the client or server sides.

If you're not familiar with ssh, it's the name of both a command and a network protocol that let you securely communicate with another computer. To use it with Mercurial, you'll be setting up one or more user accounts on a server so that remote users can log in and execute commands.

(If you are familiar with ssh, you'll probably find some of the material that follows to be elementary in nature.)

How to read and write ssh URLs

An ssh URL tends to look like this:

ssh://bos@hg.serpentine.com:22/hg/hgbook

The “

bos@” component indicates what username to log into the server as. You can leave this out if the remote username is the same as your local username.The “

hg.serpentine.com” gives the hostname of the server to log into.The “:22” identifies the port number to connect to the server on. The default port is 22, so you only need to specify a colon and port number if you're not using port 22.

The remainder of the URL is the local path to the repository on the server.

There's plenty of scope for confusion with the path component of ssh URLs, as there is no standard way for tools to interpret it. Some programs behave differently than others when dealing with these paths. This isn't an ideal situation, but it's unlikely to change. Please read the following paragraphs carefully.

Mercurial treats the path to a repository on the server as

relative to the remote user's home directory. For example, if

user foo on the server has a home directory

of /home/foo, then an

ssh URL that contains a path component of bar really

refers to the directory /home/foo/bar.

If you want to specify a path relative to another user's

home directory, you can use a path that starts with a tilde

character followed by the user's name (let's call them

otheruser), like this.

ssh://server/~otheruser/hg/repo

And if you really want to specify an absolute path on the server, begin the path component with two slashes, as in this example.

ssh://server//absolute/path

Finding an ssh client for your system

Almost every Unix-like system comes with OpenSSH

preinstalled. If you're using such a system, run

which ssh to find out if the

ssh command is installed (it's usually in

/usr/bin). In the

unlikely event that it isn't present, take a look at your

system documentation to figure out how to install it.

On Windows, the TortoiseHg package is bundled with a version of Simon Tatham's excellent plink command, and you should not need to do any further configuration.

Generating a key pair

To avoid the need to repetitively type a password every time you need to use your ssh client, I recommend generating a key pair.

On a Unix-like system, the ssh-keygen command will do the trick.

On Windows, if you're using TortoiseHg, you may need to download a command named puttygen from the PuTTY web site to generate a key pair. See the puttygen documentation for details of how use the command.

When you generate a key pair, it's usually highly advisable to protect it with a passphrase. (The only time that you might not want to do this is when you're using the ssh protocol for automated tasks on a secure network.)

Simply generating a key pair isn't enough, however.

You'll need to add the public key to the set of authorised

keys for whatever user you're logging in remotely as. For

servers using OpenSSH (the vast majority), this will mean

adding the public key to a list in a file called authorized_keys in their .ssh

directory.

On a Unix-like system, your public key will have a

.pub extension. If you're using

puttygen on Windows, you can save the

public key to a file of your choosing, or paste it from the

window it's displayed in straight into the authorized_keys file.

Using an authentication agent

An authentication agent is a daemon that stores passphrases in memory (so it will forget passphrases if you log out and log back in again). An ssh client will notice if it's running, and query it for a passphrase. If there's no authentication agent running, or the agent doesn't store the necessary passphrase, you'll have to type your passphrase every time Mercurial tries to communicate with a server on your behalf (e.g. whenever you pull or push changes).

The downside of storing passphrases in an agent is that it's possible for a well-prepared attacker to recover the plain text of your passphrases, in some cases even if your system has been power-cycled. You should make your own judgment as to whether this is an acceptable risk. It certainly saves a lot of repeated typing.

On Unix-like systems, the agent is called ssh-agent, and it's often run automatically for you when you log in. You'll need to use the ssh-add command to add passphrases to the agent's store.

On Windows, if you're using TortoiseHg, the pageant command acts as the agent. As with puttygen, you'll need to download pageant from the PuTTY web site and read its documentation. The pageant command adds an icon to your system tray that will let you manage stored passphrases.

Configuring the server side properly

Because ssh can be fiddly to set up if you're new to it, a variety of things can go wrong. Add Mercurial on top, and there's plenty more scope for head-scratching. Most of these potential problems occur on the server side, not the client side. The good news is that once you've gotten a configuration working, it will usually continue to work indefinitely.

Before you try using Mercurial to talk to an ssh server, it's best to make sure that you can use the normal ssh or putty command to talk to the server first. If you run into problems with using these commands directly, Mercurial surely won't work. Worse, it will obscure the underlying problem. Any time you want to debug ssh-related Mercurial problems, you should drop back to making sure that plain ssh client commands work first, before you worry about whether there's a problem with Mercurial.

The first thing to be sure of on the server side is that you can actually log in from another machine at all. If you can't use ssh or putty to log in, the error message you get may give you a few hints as to what's wrong. The most common problems are as follows.

If you get a “connection refused” error, either there isn't an SSH daemon running on the server at all, or it's inaccessible due to firewall configuration.

If you get a “no route to host” error, you either have an incorrect address for the server or a seriously locked down firewall that won't admit its existence at all.

If you get a “permission denied” error, you may have mistyped the username on the server, or you could have mistyped your key's passphrase or the remote user's password.

In summary, if you're having trouble talking to the server's ssh daemon, first make sure that one is running at all. On many systems it will be installed, but disabled, by default. Once you're done with this step, you should then check that the server's firewall is configured to allow incoming connections on the port the ssh daemon is listening on (usually 22). Don't worry about more exotic possibilities for misconfiguration until you've checked these two first.

If you're using an authentication agent on the client side to store passphrases for your keys, you ought to be able to log into the server without being prompted for a passphrase or a password. If you're prompted for a passphrase, there are a few possible culprits.

If you're being prompted for the remote user's password, there are another few possible problems to check.

Either the user's home directory or their

.sshdirectory might have excessively liberal permissions. As a result, the ssh daemon will not trust or read theirauthorized_keysfile. For example, a group-writable home or.sshdirectory will often cause this symptom.The user's

authorized_keysfile may have a problem. If anyone other than the user owns or can write to that file, the ssh daemon will not trust or read it.

In the ideal world, you should be able to run the following command successfully, and it should print exactly one line of output, the current date and time.

ssh myserver date

If, on your server, you have login scripts that print

banners or other junk even when running non-interactive

commands like this, you should fix them before you continue,

so that they only print output if they're run interactively.

Otherwise these banners will at least clutter up Mercurial's

output. Worse, they could potentially cause problems with

running Mercurial commands remotely. Mercurial tries to

detect and ignore banners in non-interactive

ssh sessions, but it is not foolproof. (If

you're editing your login scripts on your server, the usual

way to see if a login script is running in an interactive

shell is to check the return code from the command

tty -s.)

Once you've verified that plain old ssh is working with your server, the next step is to ensure that Mercurial runs on the server. The following command should run successfully:

ssh myserver hg version

If you see an error message instead of normal hg version output, this is usually

because you haven't installed Mercurial to /usr/bin. Don't worry if this

is the case; you don't need to do that. But you should check

for a few possible problems.

Is Mercurial really installed on the server at all? I know this sounds trivial, but it's worth checking!

Maybe your shell's search path (usually set via the

PATHenvironment variable) is simply misconfigured.Perhaps your

PATHenvironment variable is only being set to point to the location of the hg executable if the login session is interactive. This can happen if you're setting the path in the wrong shell login script. See your shell's documentation for details.The

PYTHONPATHenvironment variable may need to contain the path to the Mercurial Python modules. It might not be set at all; it could be incorrect; or it may be set only if the login is interactive.

If you can run hg version

over an ssh connection, well done! You've got the server and

client sorted out. You should now be able to use Mercurial to

access repositories hosted by that username on that server.

If you run into problems with Mercurial and ssh at this point,

try using the --debug

option to get a clearer picture of what's going on.

Using compression with ssh

Mercurial does not compress data when it uses the ssh protocol, because the ssh protocol can transparently compress data. However, the default behavior of ssh clients is not to request compression.

Over any network other than a fast LAN (even a wireless network), using compression is likely to significantly speed up Mercurial's network operations. For example, over a WAN, someone measured compression as reducing the amount of time required to clone a particularly large repository from 51 minutes to 17 minutes.

Both ssh and plink

accept a -C option which

turns on compression. You can easily edit your ~/.hgrc to enable compression for

all of Mercurial's uses of the ssh protocol. Here is how to

do so for regular ssh on Unix-like systems,

for example.

[ui] ssh = ssh -C

If you use ssh on a

Unix-like system, you can configure it to always use

compression when talking to your server. To do this, edit

your .ssh/config file

(which may not yet exist), as follows.

Host hg Compression yes HostName hg.example.com

This defines a hostname alias,

hg. When you use that hostname on the

ssh command line or in a Mercurial

ssh-protocol URL, it will cause

ssh to connect to

hg.example.com and use compression. This

gives you both a shorter name to type and compression, each of

which is a good thing in its own right.

Serving over HTTP using CGI

The simplest way to host one or more repositories in a permanent way is to use a web server and Mercurial's CGI support.

Depending on how ambitious you are, configuring Mercurial's CGI interface can take anything from a few moments to several hours.

We'll begin with the simplest of examples, and work our way towards a more complex configuration. Even for the most basic case, you're almost certainly going to need to read and modify your web server's configuration.

Web server configuration checklist

Before you continue, do take a few moments to check a few aspects of your system's setup.

Do you have a web server installed at all? Mac OS X and some Linux distributions ship with Apache, but many other systems may not have a web server installed.

If you have a web server installed, is it actually running? On most systems, even if one is present, it will be disabled by default.

Is your server configured to allow you to run CGI programs in the directory where you plan to do so? Most servers default to explicitly disabling the ability to run CGI programs.

If you don't have a web server installed, and don't have

substantial experience configuring Apache, you should consider

using the lighttpd web server instead of

Apache. Apache has a well-deserved reputation for baroque and

confusing configuration. While lighttpd is

less capable in some ways than Apache, most of these

capabilities are not relevant to serving Mercurial

repositories. And lighttpd is undeniably

much easier to get started with than

Apache.

Basic CGI configuration

On Unix-like systems, it's common for users to have a

subdirectory named something like public_html in their home

directory, from which they can serve up web pages. A file

named foo in this directory will be

accessible at a URL of the form

http://www.example.com/username/foo.

To get started, find the hgweb.cgi script that should be

present in your Mercurial installation. If you can't quickly

find a local copy on your system, simply download one from the

master Mercurial repository at http://www.selenic.com/repo/hg/raw-file/tip/hgweb.cgi.

You'll need to copy this script into your public_html directory, and

ensure that it's executable.

cp .../hgweb.cgi ~/public_html chmod 755 ~/public_html/hgweb.cgi

The 755 argument to

chmod is a little more general than just

making the script executable: it ensures that the script is

executable by anyone, and that “group” and

“other” write permissions are

not set. If you were to leave those

write permissions enabled, Apache's suexec

subsystem would likely refuse to execute the script. In fact,

suexec also insists that the

directory in which the script resides

must not be writable by others.

chmod 755 ~/public_html

What could possibly go wrong?

Once you've copied the CGI script into place,

go into a web browser, and try to open the URL

http://myhostname/~myuser/hgweb.cgi,

but brace yourself for instant failure.

There's a high probability that trying to visit this URL

will fail, and there are many possible reasons for this. In

fact, you're likely to stumble over almost every one of the

possible errors below, so please read carefully. The

following are all of the problems I ran into on a system

running Fedora 7, with a fresh installation of Apache, and a

user account that I created specially to perform this

exercise.

Your web server may have per-user directories disabled.

If you're using Apache, search your config file for a

UserDir directive. If there's none

present, per-user directories will be disabled. If one

exists, but its value is disabled, then

per-user directories will be disabled. Otherwise, the

string after UserDir gives the name of

the subdirectory that Apache will look in under your home

directory, for example public_html.

Your file access permissions may be too restrictive.

The web server must be able to traverse your home directory

and directories under your public_html directory, and

read files under the latter too. Here's a quick recipe to

help you to make your permissions more appropriate.

chmod 755 ~ find ~/public_html -type d -print0 | xargs -0r chmod 755 find ~/public_html -type f -print0 | xargs -0r chmod 644

The other possibility with permissions is that you might

get a completely empty window when you try to load the

script. In this case, it's likely that your access

permissions are too permissive. Apache's

suexec subsystem won't execute a script

that's group- or world-writable, for example.

Your web server may be configured to disallow execution of CGI programs in your per-user web directory. Here's Apache's default per-user configuration from my Fedora system.

<Directory /home/*/public_html>

AllowOverride FileInfo AuthConfig Limit

Options MultiViews Indexes SymLinksIfOwnerMatch IncludesNoExec

<Limit GET POST OPTIONS>

Order allow,deny

Allow from all

</Limit>

<LimitExcept GET POST OPTIONS>

Order deny,allow Deny from all

</LimitExcept>

</Directory>If you find a similar-looking

Directory group in your Apache

configuration, the directive to look at inside it is

Options. Add ExecCGI

to the end of this list if it's missing, and restart the web

server.

If you find that Apache serves you the text of the CGI script instead of executing it, you may need to either uncomment (if already present) or add a directive like this.

AddHandler cgi-script .cgi

The next possibility is that you might be served with a

colourful Python backtrace claiming that it can't import a

mercurial-related module. This is

actually progress! The server is now capable of executing

your CGI script. This error is only likely to occur if

you're running a private installation of Mercurial, instead

of a system-wide version. Remember that the web server runs

the CGI program without any of the environment variables

that you take for granted in an interactive session. If

this error happens to you, edit your copy of hgweb.cgi and follow the

directions inside it to correctly set your

PYTHONPATH environment variable.

Finally, you are certain to be

served with another colourful Python backtrace: this one

will complain that it can't find /path/to/repository. Edit

your hgweb.cgi script

and replace the /path/to/repository string

with the complete path to the repository you want to serve

up.

At this point, when you try to reload the page, you should be presented with a nice HTML view of your repository's history. Whew!

Configuring lighttpd

To be exhaustive in my experiments, I tried configuring

the increasingly popular lighttpd web

server to serve the same repository as I described with

Apache above. I had already overcome all of the problems I

outlined with Apache, many of which are not server-specific.

As a result, I was fairly sure that my file and directory

permissions were good, and that my hgweb.cgi script was properly

edited.

Once I had Apache running, getting

lighttpd to serve the repository was a

snap (in other words, even if you're trying to use

lighttpd, you should read the Apache

section). I first had to edit the

mod_access section of its config file to

enable mod_cgi and

mod_userdir, both of which were disabled

by default on my system. I then added a few lines to the

end of the config file, to configure these modules.

userdir.path = "public_html"

cgi.assign = (".cgi" => "" )With this done, lighttpd ran

immediately for me. If I had configured

lighttpd before Apache, I'd almost

certainly have run into many of the same system-level

configuration problems as I did with Apache. However, I

found lighttpd to be noticeably easier to

configure than Apache, even though I've used Apache for over

a decade, and this was my first exposure to

lighttpd.

Sharing multiple repositories with one CGI script

The hgweb.cgi script

only lets you publish a single repository, which is an

annoying restriction. If you want to publish more than one

without wracking yourself with multiple copies of the same

script, each with different names, a better choice is to use

the hgwebdir.cgi

script.

The procedure to configure hgwebdir.cgi is only a little more

involved than for hgweb.cgi. First, you must obtain

a copy of the script. If you don't have one handy, you can

download a copy from the master Mercurial repository at http://www.selenic.com/repo/hg/raw-file/tip/hgwebdir.cgi.

You'll need to copy this script into your public_html directory, and

ensure that it's executable.

cp .../hgwebdir.cgi ~/public_html chmod 755 ~/public_html ~/public_html/hgwebdir.cgi

With basic configuration out of the way, try to

visit http://myhostname/~myuser/hgwebdir.cgi

in your browser. It should

display an empty list of repositories. If you get a blank

window or error message, try walking through the list of

potential problems in the section called “What could possibly go

wrong?”.

The hgwebdir.cgi

script relies on an external configuration file. By default,

it searches for a file named hgweb.config in the same directory

as itself. You'll need to create this file, and make it

world-readable. The format of the file is similar to a

Windows “ini” file, as understood by Python's

ConfigParser

[web:configparser] module.

The easiest way to configure hgwebdir.cgi is with a section

named collections. This will automatically

publish every repository under the

directories you name. The section should look like

this:

[collections] /my/root = /my/root

Mercurial interprets this by looking at the directory name

on the right hand side of the

“=” sign; finding repositories

in that directory hierarchy; and using the text on the

left to strip off matching text from the

names it will actually list in the web interface. The

remaining component of a path after this stripping has

occurred is called a “virtual path”.

Given the example above, if we have a

repository whose local path is /my/root/this/repo, the CGI

script will strip the leading /my/root from the name, and

publish the repository with a virtual path of this/repo. If the base URL for

our CGI script is

http://myhostname/~myuser/hgwebdir.cgi, the

complete URL for that repository will be

http://myhostname/~myuser/hgwebdir.cgi/this/repo.

If we replace /my/root on the left hand side

of this example with /my, then hgwebdir.cgi will only strip off

/my from the repository

name, and will give us a virtual path of root/this/repo instead of

this/repo.

The hgwebdir.cgi

script will recursively search each directory listed in the

collections section of its configuration

file, but it will not recurse into the

repositories it finds.

The collections mechanism makes it easy

to publish many repositories in a “fire and

forget” manner. You only need to set up the CGI

script and configuration file one time. Afterwards, you can

publish or unpublish a repository at any time by simply moving

it into, or out of, the directory hierarchy in which you've

configured hgwebdir.cgi to

look.

Explicitly specifying which repositories to publish

In addition to the collections

mechanism, the hgwebdir.cgi script allows you

to publish a specific list of repositories. To do so,

create a paths section, with contents of

the following form.

[paths] repo1 = /my/path/to/some/repo repo2 = /some/path/to/another

In this case, the virtual path (the component that will appear in a URL) is on the left hand side of each definition, while the path to the repository is on the right. Notice that there does not need to be any relationship between the virtual path you choose and the location of a repository in your filesystem.

If you wish, you can use both the

collections and paths

mechanisms simultaneously in a single configuration

file.

Downloading source archives

Mercurial's web interface lets users download an archive of any revision. This archive will contain a snapshot of the working directory as of that revision, but it will not contain a copy of the repository data.

By default, this feature is not enabled. To enable it,

you'll need to add an allow_archive item to the

web section of your ~/.hgrc; see below for details.

Web configuration options

Mercurial's web interfaces (the hg

serve command, and the hgweb.cgi and hgwebdir.cgi scripts) have a

number of configuration options that you can set. These

belong in a section named web.

allow_archive: Determines which (if any) archive download mechanisms Mercurial supports. If you enable this feature, users of the web interface will be able to download an archive of whatever revision of a repository they are viewing. To enable the archive feature, this item must take the form of a sequence of words drawn from the list below.If you provide an empty list, or don't have an

allow_archiveentry at all, this feature will be disabled. Here is an example of how to enable all three supported formats.[web] allow_archive = bz2 gz zip

allowpull: Boolean. Determines whether the web interface allows remote users to hg pull and hg clone this repository over HTTP. If set tonoorfalse, only the “human-oriented” portion of the web interface is available.contact: String. A free-form (but preferably brief) string identifying the person or group in charge of the repository. This often contains the name and email address of a person or mailing list. It often makes sense to place this entry in a repository's own.hg/hgrcfile, but it can make sense to use in a global~/.hgrcif every repository has a single maintainer.maxchanges: Integer. The default maximum number of changesets to display in a single page of output.maxfiles: Integer. The default maximum number of modified files to display in a single page of output.stripes: Integer. If the web interface displays alternating “stripes” to make it easier to visually align rows when you are looking at a table, this number controls the number of rows in each stripe.style: Controls the template Mercurial uses to display the web interface. Mercurial ships with several web templates.You can also specify a custom template of your own; see Chapter 11, Customizing the output of Mercurial for details. Here, you can see how to enable the

gitwebstyle.[web] style = gitweb

templates: Path. The directory in which to search for template files. By default, Mercurial searches in the directory in which it was installed.

If you are using hgwebdir.cgi, you can place a few

configuration items in a web

section of the hgweb.config file instead of a

~/.hgrc file, for

convenience. These items are motd and style.

Options specific to an individual repository

A few web configuration

items ought to be placed in a repository's local .hg/hgrc, rather than a user's

or global ~/.hgrc.

Options specific to the hg serve command

Some of the items in the web section of a ~/.hgrc file are only for use

with the hg serve

command.

accesslog: Path. The name of a file into which to write an access log. By default, the hg serve command writes this information to standard output, not to a file. Log entries are written in the standard “combined” file format used by almost all web servers.address: String. The local address on which the server should listen for incoming connections. By default, the server listens on all addresses.errorlog: Path. The name of a file into which to write an error log. By default, the hg serve command writes this information to standard error, not to a file.ipv6: Boolean. Whether to use the IPv6 protocol. By default, IPv6 is not used.port: Integer. The TCP port number on which the server should listen. The default port number used is 8000.

Choosing the right ~/.hgrc file to add web items to

It is important to remember that a web server like

Apache or lighttpd will run under a user

ID that is different to yours. CGI scripts run by your

server, such as hgweb.cgi, will usually also run

under that user ID.

If you add web items to

your own personal ~/.hgrc file, CGI scripts won't read that

~/.hgrc file. Those

settings will thus only affect the behavior of the hg serve command when you run it.

To cause CGI scripts to see your settings, either create a

~/.hgrc file in the

home directory of the user ID that runs your web server, or

add those settings to a system-wide hgrc file.

System-wide configuration

On Unix-like systems shared by multiple users (such as a server to which people publish changes), it often makes sense to set up some global default behaviors, such as what theme to use in web interfaces.

If a file named /etc/mercurial/hgrc

exists, Mercurial will read it at startup time and apply any

configuration settings it finds in that file. It will also look

for files ending in a .rc extension in a

directory named /etc/mercurial/hgrc.d, and

apply any configuration settings it finds in each of those

files.

Making Mercurial more trusting

One situation in which a global hgrc

can be useful is if users are pulling changes owned by other

users. By default, Mercurial will not trust most of the

configuration items in a .hg/hgrc file

inside a repository that is owned by a different user. If we

clone or pull changes from such a repository, Mercurial will

print a warning stating that it does not trust their

.hg/hgrc.

If everyone in a particular Unix group is on the same team

and should trust each other's

configuration settings, or we want to trust particular users,

we can override Mercurial's skeptical defaults by creating a

system-wide hgrc file such as the

following:

# Save this as e.g. /etc/mercurial/hgrc.d/trust.rc [trusted] # Trust all entries in any hgrc file owned by the "editors" or # "www-data" groups. groups = editors, www-data # Trust entries in hgrc files owned by the following users. users = apache, bobo

![[Tip]](/support/figs/tip.png)

![[Note]](/support/figs/note.png)

Want to stay up to date? Subscribe to the comment feed for

Want to stay up to date? Subscribe to the comment feed for